Caucasus Hunter-Gatherers: DNA, Pillars, and Prehistory

By Mehmet Kurtkaya

There is one subject that captivates history enthusiasts and some professionals alike: How can we explain the similarities between ancient cultures in distant corners of the world?

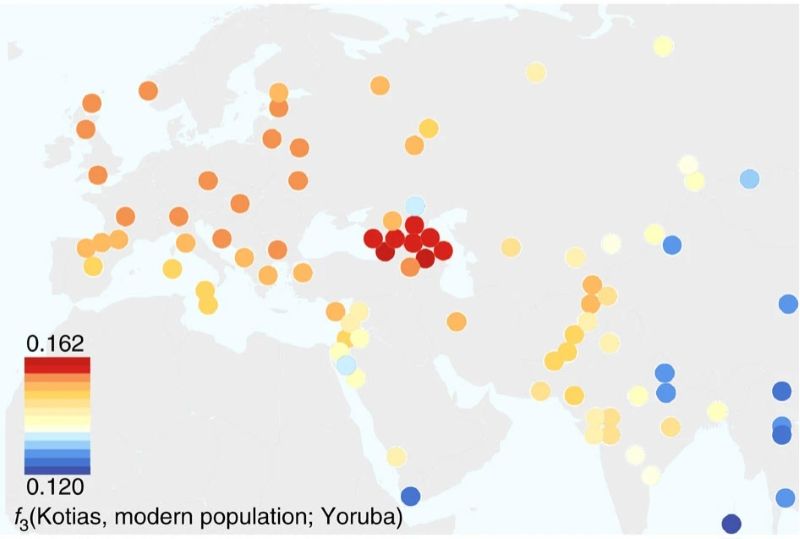

Thanks to the science of archaeogenetics, some previously unknown ancestries were uncovered. One of them, Caucasus hunter-gatherers (CHG), represents one of the most important ancestries detected through ancient DNA research. Archaeology can identify material cultures—especially from grave goods—and analyze similarities between them to classify them, but it cannot pinpoint the people involved, their mixing, or their migrations with the precision that archaeogenetics provides. Moreover, many ancient peoples were unknown to archaeology until archaeogenetic studies analyzed DNA from human remains and brought them to light.

Caucasus Hunter-Gatherers: Ancient Ancestors, Modern Legacy

Caucasus hunter-gatherer (CHG) ancestry—first identified in a 13,000-year-old sample—represents one of Eurasia's most influential ancient populations, though its carriers remain shrouded in prehistory.

Genetics alone doesn't dictate language or civilization, but it's a vital clue in comparative historical analysis. The Wikipedia entry on CHG captures this well, documenting how this ancestry fueled early Indo-European expansions and left its mark on disparate cultures—from Central Asia's Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex to Bronze Age Crete's Minoans.

Yet that summary misses the real mystery: ancient DNA from T-pillar-era sites—Boncuklu Tarla, Nemrik—reveals Caucasus hunter-gatherer ancestry already woven into Anatolia's earliest populations. One study claims it surged from the Zagros highlands centuries before Göbekli Tepe, igniting fierce debate. The timing may be disputed, but this fusion forged a lineage whose cultural fingerprints last millennia.

CHG and the Indo-European Homeland

Before diving deeper into Anatolia, let's follow CHG's broader impact. CHG's legacy extends to Indo-European origins. The ancestors of these speakers carried significant Caucasus hunter-gatherer ancestry in a well-established mix with Eastern Hunter-Gatherers; only the homeland's location remains disputed. Paul Heggarty's 2023 study places it south of the Caucasus; Lazaridis et al.'s 2025 research relocates it to the Lower Volga around 4000 BCE.

Indo-European languages spread via the nearby Yamnaya culture. As one researcher reflected: "Suppose the Yamnaya had a different culture. Suppose they had cremated their dead. Chances are, we wouldn't even know about this crucial culture in human history." Instead, their kurgans preserved them; genetics revealed their legacy.

Today, over 2 billion people speak languages from this CHG-infused lineage. While millennia have transformed those languages beyond recognition, the ancestry remains—a persistent signal through the noise of history.

CHG Migration into Anatolia

Anatolian ancient DNA samples show that Caucasus hunter-gatherer ancestry is deeply linked to Iranian Neolithic ancestry, and samples from Turkey reveal Zagros/Iranian Neolithic-related CHG ancestry. The article The South Caucasus from the Upper Palaeolithic to the Neolithic: Intersection of the genetic and archaeological data shows that the people with CHG ancestry from Iran migrated to Anatolia and mixed with local populations.

This migration was an ongoing process and is estimated to have started centuries before the appearance of Göbekli Tepe per "The spatiotemporal patterns of major human admixture events during the European Holocene", Manjusha Chintalapati et al. According to the paper Iran Neolithic farmer-related gene flow occurred ~10,900 BCE (12,200–9600 BCE). This admixture predates the earliest Anatolian farmers and postdates the local Epipaleolithic hunter-gatherers (AHG) who lacked CHG ancestry at ~13,000 BCE.

Before listing individual studies for many ancient sites in Southeast Anatolia with more precise info, I would like to recommend an interesting article from 2012 on some of their cultural aspects: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235799794_The_role_of_cult_and_feasting_in_the_emergence_of_Neolithic_communities_New_evidence_from_Gobekli_Tepe_south-eastern_Turkey, written by Oliver Dietrich, Jens Notroff, Manfred Heun, and Klaus Schmidt.

Göbekli Tepe is not the only site with T-stone pillars or stone totem poles. In this broad region, a few other such sites exist. However, it was the most complex site ever constructed by hunter-gatherers and it was the first that was excavated. Many publications analyzed different aspects of the site in the last two decades. Göbekli Tepe, Nevalı Çori and similar sites—represent the most complex hunter-gatherer constructions in history.

Archaeologists note that the immense effort required to build it may have spurred the advent of agriculture in the region—the first time anywhere in the world. The late Klaus Schmidt, who initiated excavations at Göbekli Tepe and worked there for decades as the site's leading expert, highlighted the social hierarchy and labor organization needed to create these monumental circular enclosures, which were primarily used for rituals. He also emphasized the symbolism in the T-shaped pillars, depicted through animals and abstract motifs. These collective symbols and images are not a language in the traditional sense, but all experts agree that they conveyed profound meaning to the hunter-gatherers who created them.

Göbekli Tepe has drawn comparisons to nearby sites known collectively as Taş Tepeler, including Karahan Tepe. That said, there are some intriguing parallels with cultures from the Ural Mountains in Russia to Native American totem poles in the Pacific Northwest, including their mythologies and social hierarchies represented via totem poles. While these comparisons come from archaeologists, amateurs and independent researchers have also drawn links to cultures worldwide. We also know that Göbekli Tepe featured a skull cult and excarnation practices, including sky burial—rituals still found in the Himalayas today.

DNA from one T-Pillar Site, Nevali Çori and other contemporaneous sites in Southeastern Anatolia

We lack genetic data from Göbekli Tepe itself, but we have data from the nearby contemporaneous sites like Boncuklu Tarla and from many other sites like Nevalı Çori in Anatolia.

Archaeogenetic findings from ancient Anatolian sites reveal a clear cline from East to West. DNA samples from various sites show that Iran-related Caucasus hunter-gatherer ancestry entered Anatolia from the east and spread westward. Older Anatolian Hunter-Gatherers samples lacked CHG ancestry, and none of them built such structures.

Let's examine what the published research says. Genomic data are from sites such as Boncuklu Tarla, Çayönü, Aşıklı Höyük, Nemrik 9, and Nevalı Çori.

Boncuklu Tarla is about 200 kilometers from Göbekli Tepe. Skourtanioti et al. 2022 uses qpAdm models that show Boncuklu Tarla can be modeled as a mix of AHG and Iran_N, proving CHG ancestry at the site.

Çayönü, a major early Neolithic village in Upper Mesopotamia (~9500–7000 BCE), sits just 200 km from Göbekli Tepe and gives us our best DNA clues from that era. Samples from around 8500–7500 BCE show about 33% ancestry linked to the Zagros Mountains and CHG, blended with local Anatolian and Levantine roots—pointing to eastern migrants arriving right when Göbekli Tepe's massive stone circles were going up (~9500–8800 BCE). Even though these genomes are a few centuries later, they capture the same early farming culture of settled villages, basic homes, and early animal herding that likely fueled the ritual gatherings at Göbekli Tepe (Altınışık et al., 2022, Science Advances).

Complementing these insights, the definitive 2023 study on Nevalı Çori —a flagship stone totem pole site just 60 km from Göbekli Tepe— provides direct genetic evidence of CHG/Iranian Neolithic ancestry during the middle PPNB (~8300–7900 BCE). At Nevalı Çori, similar enclosures housed anthropomorphic pillars, underscoring shared labor and symbolism (Hauptmann 1993).

The individual NEV009 is shifted toward the direction of the Early Holocene Iranian (Neolithic Iran; “Iran N”) and Caucasian HG (“CHG”) individuals (Wang et al., 2023, PNAS).

Based on the above research papers we see that Southeastern Anatolia had many sites with CHG ancestry, showing an influx of people from Iran. Hence the people in the region were a mix of local and migrating groups. There is no question that any migrating group interbreeding with a local population will have a cultural and linguistic effect; the question is which specific practices or ideologies were introduced in this case.

| Site | Distance to Göbekli Tepe | Date (BCE) | CHG/Iran_N Ancestry | Key Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boncuklu Tarla | ~200 km | 10,500–9,500 | ~20-30% (qpAdm: AHG + Iran_N) | Skourtanioti et al. (2020/22) |

| Çayönü | ~200 km | 8,500–7,500 | ~33% Zagros-related | Altınışık et al. (2022) |

| Nevalı Çori | ~60 km | 8,300–7,900 | Shifted toward Iran_N/CHG (NEV009) | Wang et al. (2023) |

Some Parallels Across Eurasia

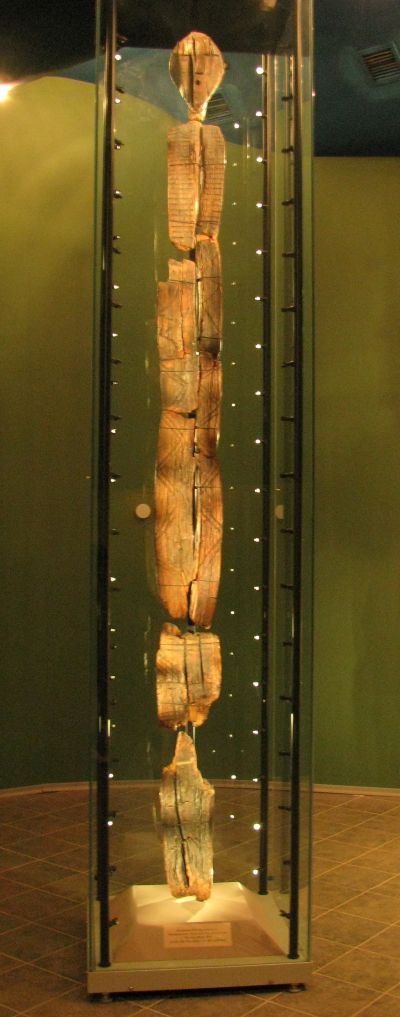

For example, In their 2018 Antiquity article, Zhilin et al. date the Shigir Idol to ~9600 cal BC—contemporary with Göbekli Tepe’s early phase. They identify Southeast Anatolia (including Nevalı Çori and Göbekli Tepe) and the Urals as the only Early Holocene regions with monumental anthropomorphic sculptures and animal motifs. Both sites show parallel forms: Shigir’s 5.3 m wooden plank with faces and zig-zags, and Göbekli Tepe’s T-shaped pillars with arms, belts, and fauna—signaling a shared shift to fixed ritual art among hunter-gatherers.

The Shigir Idol wooden totem pole as old as Göbekli Tepe was miraculously preserved in a peat bog, creating an ideal environment for conservation. This is crucial because peoples across Eurasia may have built similar wooden structures to the Shigir Idol or Göbekli Tepe, but we will never know, as they would have decayed. In contrast, Göbekli Tepe, Karahan Tepe, and nearby circular stone enclosures have endured the test of the time.

These topics are complex and intricate, so I will limit myself to covering the origins of the people in the region. I draw on archaeology and archaeogenetics in tandem, after noting similarities in beliefs across other parts of Eurasia. I will cite only major findings from research papers and academics to address the core question: Who built these monumental stone centers in Southeast Anatolia?

Conclusion: Migrations and Mixing

To Sum Up CHG’s Legacy in Anatolia:

- Neolithic Revolution: Anatolian Neolithic farmers had CHG ancestry. This is an established fact through many archaeogenetics studies for years. They were not local-only populations, they were mixed with incoming groups.

- The people who built stone totem pole at Nevalı Çori had CHG ancestry (via Iran_N).

CHG is a genetic cluster, not a single culture. The key here is the existence of a mixture of local and migrating populations. Thanks to archaeogenetics, the study of history has shifted: Local innovation models are no longer the default.

The influx of CHG ancestry correlates precisely with the emergence of unprecedented cultural complexity in Southeastern Anatolia. While correlation is not causation, the temporal and genetic data position this migration as a potential catalyst for sites like Göbekli Tepe, Nevalı Çori and others.

Let's examine the alternatives to confirm the CHG migration as the most plausible explanation for the appearance of this new culture.

Local contemporaneous sites like Körtik Tepe lacked monumental buildings, coordinated large-scale labor, or T-shaped pillars. There is no evidence of a gradual, local trajectory—the appearance of monumental architecture represents a cultural rupture. Thus, local autochthonous continuity is unlikely.

Levantine sites featured skull cults and communal buildings, but they lacked T-shaped pillars, the raptor/snake cosmology found in Eurasia, and the specific iconographic syntax of Göbekli Tepe.

Göbekli Tepe and its nearby stone structures stand out for their symbolism, massive labor mobilization, and social hierarchy—without parallels on this scale among Anatolian Hunter-Gatherers or Levantine populations.

While this doesn't prove CHG influence caused the stone pillar sites, it makes it a highly likely contributing factor.

The problem with current historical studies is that archaeogenetics has revealed previously unknown peoples who migrated to distant corners of the world, often mixing or interacting with locals—yet history books and academia remain wedded to the “local development” model that has prevailed for decades, if not centuries.

Who would have thought, two decades ago, that farming spread from Anatolia to Europe via the migration of Anatolian Neolithic Farmers, who mixed with the existing hunter-gatherers there? We now see a clear example of people migrating, interbreeding with locals, and bringing their technologies and cultures along. We know this with 100% certainty.

Now we know for sure that Yamnaya people migrated to Europe, Asia, and South Asia, bringing their languages, cultural influences, technologies—and linguistic elements—with them.

These are just two examples of massive migration and interbreeding events; many more have occurred, and archaeogenetics has uncovered them.

Unfortunately, this scientific revolution in archaeogenetics is still not fully integrated into multidisciplinary studies, which remain lacking in most cases.

Still, let's not get carried away—the puzzle is immensely complex, both geographically and temporally. Therefore, simply placing one piece here or there won't solve it. But there is a silver lining: What makes the puzzle difficult will also yield vast new information that was previously lost to the record. Writing began in Sumer and neighboring Elam 5,000 years ago, and widespread literacy only emerged in the last 2,000 years.

So, we must place many pieces on the board to solve the ancient history puzzle. We will start by positioning isolated pieces and then connect them to others, checking if they align in both space and time. Archaeogenetics is our most valuable tool, as it reveals migrations and interbreeding among peoples—events that surely shaped their languages, cultures, mythologies, and technologies.

We will treat hypotheses like puzzle pieces, testing if they match the archaeogenetic, archaeological, and linguistic data. It is a difficult task, but we now have powerful tools at our disposal. As we continue to place these pieces, guided by the light of DNA, we are not just solving a puzzle—we are reclaiming the lost narratives of the peoples who built the foundations of our world.

What we observe in the “r” sound of the word “round” across languages—one of the most basic words shared globally—is surely the echo of thousands of years of history. That's a given.

The challenge is to generate good ideas and proposals that we can test with the tools at hand, including mathematical and AI-driven linguistics.

Copy the article and paste it into any AI (Grok, Deepseek, Gemini, Qwen, Claude, Kimi, …) and ask it to verify, challenge, or expand.

AI note

I use several large language models—including Grok, DeepSeek, Kimi, and others—for research assistance, fact-checking, drafting, and cross-verification. Like all tools, they have strengths and limitations. Final responsibility for the content, interpretations, and any errors remains mine.